|

| Our benefactor. |

For one thing, I've now clocked several days during which I've both cooled my house and heated my pool simultaneously and still ended one day with a power surplus. During the sunniest days of Memorial Day Weekend, I finished just a little behind the break-even point on the first and on the second day, finished well ahead. And I did it while hosting a two-day pool party that impressed our friends.

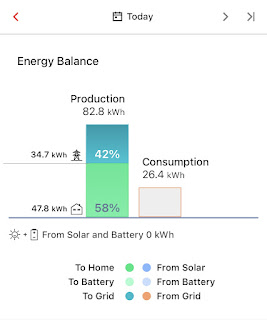

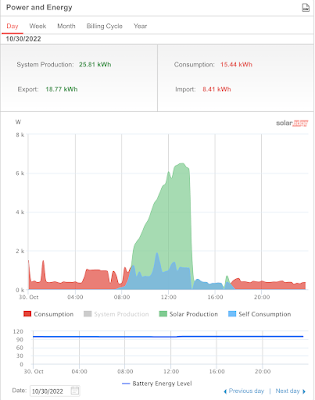

Here's what the data shows:

On May 25, my system produced 77.3 kWh while the house and pool consumed a combined 82.7 kWh. Only 13 percent of the day's power needs came from the utility grid, the rest directly from the solar array. I ran the pool heater most of the day in order to get the water temperature up to a comfortable 80 degrees.

On May 26, I only ran the pool heater for a few hours in the morning and then shut it off, which lowered the day's power needs. I ended the day generating 76.7 kWh and consuming 64.2 kWh. The next day, it was rainy, so I left the pool heater and the house air conditioners off. But for those two pool-use days, I ended the weekend consuming 147 kWh against solar generation of 154 kWh. In short, I ran those heavy-consuming items for free.

And that's important for another reason. According to my utility, CenHUD, as of May, I had a 2.8 mWh generation surplus on the books. This means I could, in theory, run both the AC and pool heater guilt-free for the better part of the summer, working against that surplus. But as it stands, I'm running both and actually making the surplus even bigger.

Also, sometime in May, we crossed the threshold of our 15th ton of carbon emissions saved and should hit 16 tons by July.

And yes, I grant that not everyone is in a position to borrow about $40,000 for something like this. Most solar households skew toward the higher income brackets. A study by the Lawrence Livermore National Lab found that in 2022 — the year I deployed my system — reported income ranging from 108 percent to 180 percent of their state's median. When only wealthy people can afford to spend money to save money on a necessity like electricity, we have a problem. But there are programs coming online now that will help lower-income families go solar via grants and low-interest loans.

The cost of electrical power isn't going to decline in any part of the country anytime soon. Demand is rising across the country and, in fact, around the world way too fast for that. The only way for a home or business to counter that trend is to reduce usage or start generating on-site from a free and sustainable power source like the sun or wind. Solar won't work in every situation, but my array is so far proving the case for rooftop solar.

While I'm at it, there's one additional new wrinkle to report. Last month, we swapped out our old 80-gallon natural gas water heater for a hybrid electric water heater with an 80-gallon tank. I was a little concerned at first. When it was installed, the weather was rainy, and it seemed like the new heater was going to consume more power than the solar array generates and thus erase all the progress I've made. But it has slowed down a bit since powering up. I'll have more to say about it as the months wear on. I'm specifically interested to see how my gas bill declines, if at all. Water heating accounts for about 15 percent of gas usage in the average U.S. home (I read that stat somewhere but now can't find the link.), while the rest goes for space heating, cooking, and drying laundry.

The up-front cost was about $8,000, and I'll get $1,000 back from the utility and then another $2,000 tax rebate from the federal government when I file next year. (Thank you Biden Administration!) I also had to hire an electrician to install an electrical sub-panel as my current basement panel was maxed out.

The gas bill has been a tough nut to crack because winters in the Hudson Valley can get incredibly cold and so there's no choice but to consume a lot of gas. The new water heater should reduce our gas consumption. I'm also likely to turn off an ornamental gas fireplace we rarely use, even in cold weather. Plus, I'd like to swap out the gas-based cooktop in the kitchen for an induction stove.

But another big upgrade is looming ahead: The two AC units out in the backyard have about one year left in their realistic operational lifespan. That means electric heat pumps are in my future, which should put a bigger dent in my natural gas footprint. But it should also increase my electrical demand. And yes, another round of tax credits will make the move a little easier on my wallet. Can the current solar array keep up? Or might I have to add some additional panels on the West side of the house? And I haven't even begun to think about an electric vehicle yet. Obviously, there will be much more to consider in the coming 12 to 18 months.

(Image of the Sun: The Sun photographed in 2010 at 304 angstroms by the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly of NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.)